The cheese craftsman

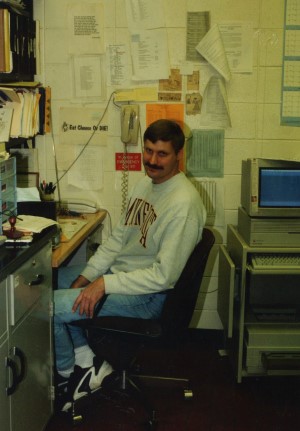

During a 40-year career, Ray Miller has shaped Minnesota’s artisanal cheese industry.

About a decade ago, Deeann Lufkin, Jackie Ohmann and Kathy Hupf had a big problem. They’d been cooking tiny amounts of cheese in their kitchens, and their friends and family couldn’t get enough of it. But they had no idea how to turn the hobby they loved into a commercial business.

Today, the three of them run CannonBelles, an award-winning artisanal cheese company that operates in Cannon Falls, Minnesota, and sells cheese across the state and beyond.

Deeann said that the magic ingredient in getting them from the stovetop to a successfully scaled-up company was the Joseph J. Warthesen Processing Center at the University of Minnesota and its coordinator for 40 years, Reynault (Ray) Miller.

Within the Department of Food Science and Nutrition, this facility is usually referred to simply as the pilot plant. When it comes to dairy, cheeses, extruded products, plant protein isolates and more, the pilot plant is a home for the department’s research and teaching. It’s also a place for established food companies and entrepreneurs alike to test their ideas, innovate and grow. For several years, Deeann, Jackie and Kathy produced their early commercial makes of cheese at the pilot plant, learning the fundamentals of proper cheesemaking from Ray.

His knowledge, ingenuity and generosity have been the beating heart of the pilot plant, and cheese is his passion. As Ray retires this month, Deeann said it’s impossible to overstate his impact on the state’s cheese industry. According to her, Ray has worked with or trained nearly every artisanal cheesemaker currently practicing their craft in Minnesota.

“We’ve all gone to the University of Minnesota to get our start,” she said. “Without Ray, Minnesota cheese would not be where it is today.”

A passion becomes a career

Ray came to cheese through family. His dad was from the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, where he worked as a cheesemaker for Kraft. When Ray was in the third grade, his dad was offered a job at the pilot plant, so the family relocated to Minnesota.

Ultimately, his dad worked in the pilot plant for 15 years, which meant Ray grew up around the place. He met the professors conducting their research there, including Dr. Howard Morris, a dairy science professor who would eventually hire Ray to work in the plant, too, starting in 1983.

“When I first started, I was learning a lot while taking food science courses at the university at night,” Ray said. “It was very hands on, almost like a position as a lab assistant.”

Meanwhile, Ray had played professional basketball in France in 1980 and 1981. While he was there, he fell in love with European cheeses.

“My favorite are alpine-style cheeses like gruyere. The cows are treated to the high-elevation foliage and grasses, and as a result, those semi-hard and hard cheeses have a lot of caramelly, nutty and fruity notes,” Ray said.

And so, his job and his passion were in sync. In 2018, he would go back to Europe for a summer and collaborate with cheesemakers in the French and Swiss Alps, exchanging knowledge and learning from one another.

As Ray’s career evolved over the years, so did the activities at the pilot plant. Research and teaching remained central, but increasingly Ray coordinated trials for both large and small companies from across the U.S. there, too. In addition to Ray’s expertise as a food technologist, the companies found the production scale of the pilot plant useful: the small ones for scaling up and the large ones for testing new ideas without the expense of temporarily shutting down or reconfiguring an industrial-sized facility of their own. This expanded mission has allowed the pilot plant to become financially self-sufficient over the past 10 to 15 years.

Dr. Job Ubbink, head of the Food Science and Nutrition department, called out that the pilot plant is an essential part of the department’s research, teaching and service to the community. And Ray’s keen interest in food science and technology combined with his orientation toward serving others has made the pilot plant successful in its mission.

“When I moved here five years ago, I had other food science department chairs asking me, ‘Is Ray Miller still there?’ He’s known around the U.S.,” Job said. “Plus, I have an affinity for gouda cheese from my home country of the Netherlands, and Ray does a great job on gouda!”

The endless mysteries of cheese

So what is it about cheese that’s held Ray’s interest for his entire career, leading him to win numerous awards? Perhaps it’s the fact that despite strict processes and clearly defined science, no two makes are ever alike.

“It’s a living system. Every lot of milk is different – different cattle, different diet, different times of year. So now you’re trying to make a consistent product with a variable starting component,” Ray explained. “Then there’s the microbiology, the flavors that emerge as the enzymes work on the protein and fat to produce different flavor compounds long after the cheese is made. It’s why an aged cheddar doesn’t taste anything like a mild cheddar. It’s the ever-living system of cheese.”

The endless variables mean that sometimes experiments go wrong. What Ray’s mentor Dr. Morris taught him is that that’s okay – desirable, even.

“In labs, when a student would forget to add a culture, Dr. Morris would say ‘That’s okay! They’re going to learn more from that mistake than they would if everything turned out well.’”

And although some experiments fail, others are a home run. For example, 11 months after Ray helped the CannonBelles team scale up their original recipe, it took first place at the American Cheese Society’s annual competition.

As Ray sat next to Deeann at the award ceremony, he wasn’t ready to stop experimenting, to stop tinkering with that ever-living system.

“He leaned over to me and said, ‘Maybe we should try adding more salt?’” she recalled.

Despite his impending retirement, Ray’s passion for innovation has continued. Just last month, Ray visited the CannonBelles facility and spotted one small tweak they could make in their process. It had an immediate positive effect, according to Deeann. Meanwhile, they told him about a new experimental cheese they were trying and he was instantly drawn into excited discussion with them.

As Deeann put it: “You just feel better and smile when you’re around him.”