New research finds that fish are likely a widespread food for wolves

As anglers rush to their favorite lakes with the hope of catching the year's first pike or walleye, researchers from the Voyageurs Wolf Project (VWP), a University of Minnesota research project in collaboration with the National Park Service, reveal that wolves also travel to their own fishing holes every year.

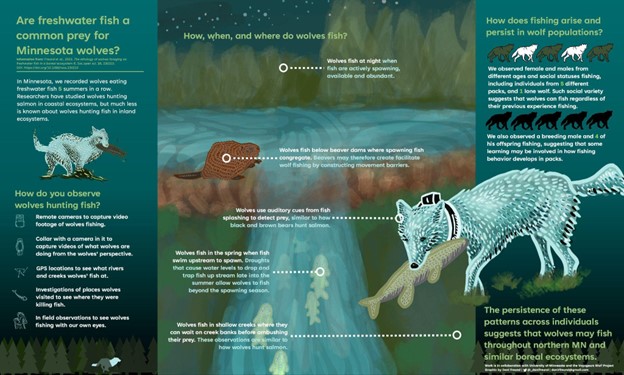

A recent VWP publication in the journal Royal Society Open documented wolves fishing every spring for five years in a row, and the group is still collecting more data.

“When we first recorded wolves fishing in 2017, we thought it was a rare observation,” explains Dani Freund, lead author on the paper and collaborator with VWP. “But after observing males and females, yearlings and adults, lone wolves and pack members fish, we think that wolves hunt spawning fish across similar boreal ecosystems, and they likely have been doing it for quite a while. We don’t think it is a new behavior.”

In VWP’s initial account of wolves fishing, published in the journal Mammalian Biology in 2018, the group only observed two wolves from the same pack catching fish one spring.

Those early observations were “very anecdotal” according to Dr. Thomas Gable, leader of VWP. “This work is more rigorous because it is over many years. We also have already recorded wolves fishing this year. So we’ve documented the behavior occurring six out of seven years since 2017.”

The robust dataset from annual observations allowed the group to gain powerful insights into the intricacies of when, where, and how wolves fish. Wolves fish at night from April to June, when fish in Minnesota swim upstream en masse and are actively spawning. Fish splash more and are distracted when they’re laying their eggs, making it easy for wolves to detect their prey and catch them.

“Wolves' main weapon is their mouth, so going after prey such as deer can cause a severe injury,” explains Freund. “Fish on the other hand can’t do much to a wolf, and wolves seem to be taking advantage of that. Some wolves seemed to completely pass up larger prey such as beaver when fish were available and abundant.”

Wolves fished in creeks, rivers, and streams less than three feet deep, and oftentimes in the shallow waters below beaver dams. The dams create barriers for fish as they swim upstream to spawn, causing a fish traffic jam that wolves use to their advantage. By directly building dams and indirectly creating fish pile-ups, beavers appear to create favorable fishing spots for wolves.

Camera trap videos recorded by VWP showed wolves waiting on creek banks and ambushing their prey by plunging their noses into the water and catching fish in their jaws — a strategy similar to how wolves hunt salmon in British Columbia and Alaska. Such observations add to growing evidence that wolf hunting behavior is more flexible than the chasing behaviors wolves are typically associated with to hunt deer, elk, and moose.

But anglers shouldn’t worry about wolves vying for their prized catch. The only fish researchers found wolves killing were suckers — a non game species that is native to Minnesota but commonly referred to as a “trash” or “rough” fish. The DNR launched a campaign in 2021 to reduce the common misrepresentation that these fish are “junk” and play important roles in the ecosystem. Although suckers are not always valued or eaten by people, they appear to be widely valued as a resource by wolves year after year.

The Voyageurs Wolf Project is funded, in part, by the Minnesota Environment and Natural Resources Trust Fund as recommended by the Legislative-Citizen Commission on Minnesota Resources (LCCMR).