Encouraging cultural roots

Vegetable Working Group volunteers aim to enhance immigrant produce

Unique recipes require specific ingredients. But for many immigrant families, culturally-specific produce is rarely found at Minnesota farmers’ markets, never mind at a commercial grocer. Those longing for home-country meals have mainly been out of luck in finding familiar foods. But a new group at the Plant Breeding Center in CFANS hopes to change that.

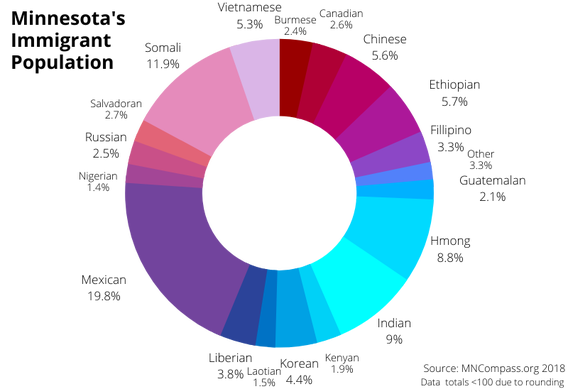

Minnesota is home to an estimated 500,000 immigrants from 25 countries, 60 percent of whom are from East Africa. Minnesota has the ninth-largest Somali population in the U.S. Many African immigrants arrive fleeing political persecution or civil war. Still, a large number also choose Minnesota for the higher education and job opportunities. Immigrant communities are a diverse group, loosely knit by cultural threads.

The Vegetable Working Group

CFANS' new Vegetable Working Group identified Minnesota’s cultural vegetable void and formed an all-volunteer group to address it. The group is composed of four graduate students and two postdoctoral researchers advised by Plant Breeding Center Director Rex Bernardo, PhD.

“I really wanted to serve our local community,” agronomy and plant genetics graduate student and working group volunteer Hannah Stoll said. “On campus, you can get disconnected from the surrounding community. The Vegetable Working Group will allow us to practice traditional plant breeding techniques in a way that truly benefits our neighbors. And while we will gain experience, this project isn’t for us. It’s for the people whom we are serving and farmers we are working alongside.”

Agronomy and plant genetics postdoctoral researcher and fellow working group volunteer Yinjie Qiu agreed. “We want to use what we’ve learned to help minority groups find and improve germplasms for those vegetables that are culturally-significant to them but are missing from local markets.”

The big chill

The challenge in growing regionally unique crops is often the weather and growing degree days. The climatic difference between Northern Africa and Minnesota is significant. Somalia, for example, rarely sees temperatures below 65°F (18°C). Its primary weather influence is the alternating extremes of rainy and dry seasons. In contrast, Minneapolis regularly experiences three consecutive months of low temperatures in the teens or single digits. Few vegetables tolerate such differences. But plant breeding for specific traits could improve their reliability.

Improving climatic tolerance works on two fronts. The first is cold hardiness where even a single early or late freezing temperature shock could kill the plant entirely. The second is winter endurance. Minnesota’s lengthy cold season requires crops to mature quickly due to the reduced number of growing degree days. Both factors are opportunities for crop improvement.

“Minnesota has a short growing season, so some African fruiting crops are not an option to grow in the field. But leafy greens hold good possibilities for climate adaptation, which is why we are starting with those,” Stoll said.

What would improvement mean?

Influencing several plant traits would make some non-native vegetables better suited to Minnesota’s climate. Specifically, increasing frost tolerance, fast maturation, and drought tolerance would represent significant progress. But it’s not just agronomic improvement this group seeks.

“We want to work with the local community to understand their preferences — taste, texture, and storage, for example. We don’t presume to know their needs and want their interests to drive our breeding efforts,” Stoll said.

Seeking sources

One unexpected challenge the group has encountered is sourcing. Specialty crops like these are not commercially grown for seed, making their genetic pool fairly limited. So the group has gotten creative.

“We’ve received seed samples from the USDA Germplasm Resources Information Network and the World Vegetable Center in Taiwan via the University of California-Davis,” Qiu said. “Having these resource networks will be a great asset.”

Communication comes first

While searching for genetic stock continues, the group’s first goal is to establish community connections. UMN Extension educator Natalie Hoidal has been a key liaison with several farmers growing specialty crops.

“We really lack information about how to grow these crops successfully in the Midwest,” Hoidal said. “For the most part, people are using varieties they've brought with them from their home countries, or varieties they've been able to access from the USDA gene banks. Most Minnesota farmers can look to decades of research to inform their management decisions, but growers who want to grow non-Euro-centric crops have had to take on all of the risk of experimentation on their own.”

The working group is planning listening sessions to gain community input and hopes to meet one on one with farmers and visit their plots to learn more about their challenges. The group acknowledges the need to get off campus and into community gardens.

“We can’t expect them to come to us,” Qiu said. “During the growing season, farmers don’t have time to take off and visit test plots on campus. We need to go to them – listen to their needs and offer to plant trials in their soil.”

The group hopes to eventually plant trial plots of improved vegetable lines at several local community gardens, allowing growers and residents to participate in the selection process and feel a sense of ownership.

Open-sourced seed

The University of Minnesota connection is essential to provide the structure and knowledge base for plant progress. Through the Plant Breeding Center, the Vegetable Working Group’s volunteers have access to top mentors, genetic tools, and experienced staff, who will provide project continuity as students come and go.

But if the group is successful with its plant improvement efforts, how will varieties be made available? Commercially bred crops are usually patented or protected, increasing the seed cost and potentially decreasing their availability.

The Vegetable Working Group’s model is entirely different. It’s a ‘by, not for’ approach. The center doesn’t intend to patent any improved vegetable seed and views varietal acceptance and accessibility as the top priorities.

“We want the immigrant communities to embrace these varieties as their own,” Qiu said. “We intend to make any improved varieties readily available and give people the full capability to perpetuate these crops. They will be available to all, not just us.”

Driven to discover

UMN’s Plant Breeding Center was established in 2020 to serve as a hub for leveraging Minnesota strengths in plant breeding research, varietal development, and graduate education.

The center is managed through the Department of Agronomy and Plant Genetics and the Department of Horticultural Science in the College of Food, Agricultural and Natural Resource Sciences.